12/08/2011

history of The Jimi Hendrix Experience

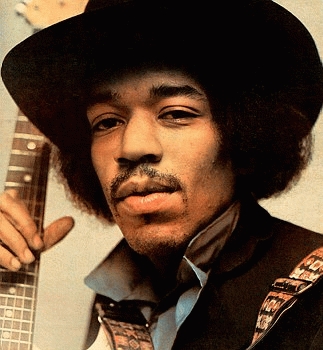

In his brief four-year reign as a superstar, Jimi Hendrix expanded the vocabulary of the electric rock guitar more than anyone before or since. Hendrix was a master at coaxing all manner of unforeseen sonics from his instrument, often with innovative amplification experiments that produced astral-quality feedback and roaring distortion. His frequent hurricane blasts of noise, and dazzling showmanship — he could and would play behind his back and with his teeth, and set his guitar on fire — has sometimes obscured his considerable gifts as a songwriter, singer, and master of a gamut of blues, R&B, and rock styles.

When Hendrix became an international superstar in 1967, it seemed as if he'd dropped out of a Martian spaceship, but in fact he'd served his apprenticeship the long, mundane way in numerous R&B acts on the chitlin circuit. During the early and mid-'60s, he worked with such R&B/soul greats as Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, and King Curtis as a backup guitarist. Occasionally he recorded as a session man (the Isley Brothers' 1964 single "Testify" is the only one of these early tracks that offers even a glimpse of his future genius). But the stars didn't appreciate his show-stealing showmanship, and Hendrix was straightjacketed by sideman roles that didn't allow him to develop as a soloist. The logical step was for Hendrix to go out on his own, which he did in New York in the mid-'60s, playing with various musicians in local clubs, and joining White blues-rock singer John Hammond, Jr.'s band for a while.

It was in a New York club that Hendrix was spotted by Animals bassist Chas Chandler. The first lineup of the Animals was about to split, and Chandler, looking to move into management, convinced Hendrix to move to London and record as a solo act in England. There a group was built around Jimi, also featuring Mitch Mitchell on drums and Noel Redding on bass, that was dubbed the Jimi Hendrix Experience. The trio became stars with astonishing speed in the U.K., where "Hey Joe," "Purple Haze," and "The Wind Cries Mary" all made the Top 10 in the first half of 1967. These tracks were also featured on their debut album, Are You Experienced?, a psychedelic meisterwerk that became a huge hit in the U.S. after Hendrix created a sensation at the Monterey Pop Festival in June of 1967.

Are You Experienced? was an astonishing debut, particularly from a young R&B veteran who had rarely sung, and apparently never written his own material, before the Experience formed. What caught most people's attention at first was his virtuosic guitar playing, which employed an arsenal of devices, including wah-wah pedals, buzzing feedback solos, crunching distorted riffs, and lightning, liquid runs up and down the scales. But Hendrix was also a first-rate songwriter, melding cosmic imagery with some surprisingly pop-savvy hooks and tender sentiments. He was also an excellent blues interpreter and passionate, engaging singer (although his gruff, throaty vocal pipes were not nearly as great assets as his instrumental skills). Are You Experienced? was psychedelia at its most eclectic, synthesizing mod pop, soul, R&B, Dylan, and the electric guitar innovations of British pioneers like Jeff Beck, Pete Townshend, and Eric Clapton.

Amazingly, Hendrix would only record three fully conceived studio albums in his lifetime. Axis: Bold as Love and the double-LP Electric Ladyland were more diffuse and experimental than Are You Experienced? On Electric Ladyland in particular, Hendrix pioneered the use of the studio itself as a recording instrument, manipulating electronics and devising overdub techniques (with the help of engineer Eddie Kramer in particular) to plot uncharted sonic territory. Not that these albums were perfect, as impressive as they were; the instrumental breaks could meander, and Hendrix's songwriting was occasionally half-baked, never matching the consistency of Are You Experienced? (although he exercised greater creative control over the later albums).

The final two years of Hendrix's life were turbulent ones musically, financially, and personally. He was embroiled in enough complicated management and record company disputes (some dating from ill-advised contracts he'd signed before the Experience formed) to keep the lawyers busy for years. He disbanded the Experience in 1969, forming the Band of Gypsies with drummer Buddy Miles and bassist Billy Cox to pursue funkier directions. He closed Woodstock with a sprawling, shaky set, redeemed by his famous machine-gun interpretation of "The Star-Spangled Banner." The rhythm section of Mitchell and Redding were underrated keys to Jimi's best work, and the Band of Gypsies ultimately couldn't measure up to the same standard, although Hendrix did record an erratic live album with them.

In early 1970, the Experience re-formed again — and disbanded again shortly afterwards. At the same time, Hendrix felt torn in many directions by various fellow musicians, record-company expectations, and management pressures, all of whom had their own ideas of what Hendrix should be doing. Coming up on two years after Electric Ladyland, a new studio album had yet to appear, although Hendrix was recording constantly during the period.

While outside parties did contribute to bogging down Hendrix's studio work, it also seems likely that Jimi himself was partly responsible for the stalemate, unable to form a permanent lineup of musicians, unable to decide what musical direction to pursue, unable to bring himself to complete another album despite jamming endlessly. A few months into 1970, Mitchell — Hendrix's most valuable musical collaborator — came back into the fold, replacing Miles in the drum chair, although Cox stayed in place. It was this trio that toured the world during Hendrix's final months.

It's extremely difficult to separate the facts of Hendrix's life from rumors and speculation. Everyone who knew him well, or claimed to know him well, has different versions of his state of mind in 1970. Critics have variously mused that he was going to go into jazz, that he was going to get deeper into the blues, that he was going to continue doing what he was doing, or that he was too confused to know what he was doing at all. The same confusion holds true for his death: contradictory versions of his final days have been given by his closest acquaintances of the time. He'd been working intermittently on a new album, tentatively titled First Ray of the New Rising Sun, when he died in London on September 18, 1970, from drug-related complications.

Hendrix recorded a massive amount of unreleased studio material during his lifetime. Much of this (as well as entire live concerts) was issued posthumously; several of the live concerts were excellent, but the studio tapes have been the focus of enormous controversy for over 20 years. These initially came out in haphazard drabs and drubs (the first, The Cry of Love, was easily the most outstanding of the lot). In the mid-'70s, producer Alan Douglas took control of these projects, posthumously overdubbing many of Hendrix's tapes with additional parts by studio musicians. In the eyes of many Hendrix fans, this was sacrilege, destroying the integrity of the work of a musician known to exercise meticulous care over the final production of his studio recordings.

Even as late as 1995, Douglas was having ex-Knack drummer Bruce Gary record new parts for the typically misbegotten compilation Voodoo Soup. After a lengthy legal dispute, the rights to Hendrix's estate, including all of his recordings, returned to Al Hendrix, the guitarist's father, in July of 1995. — Richie Unterberger

Abonați-vă la:

Postare comentarii (Atom)

Niciun comentariu:

Trimiteți un comentariu